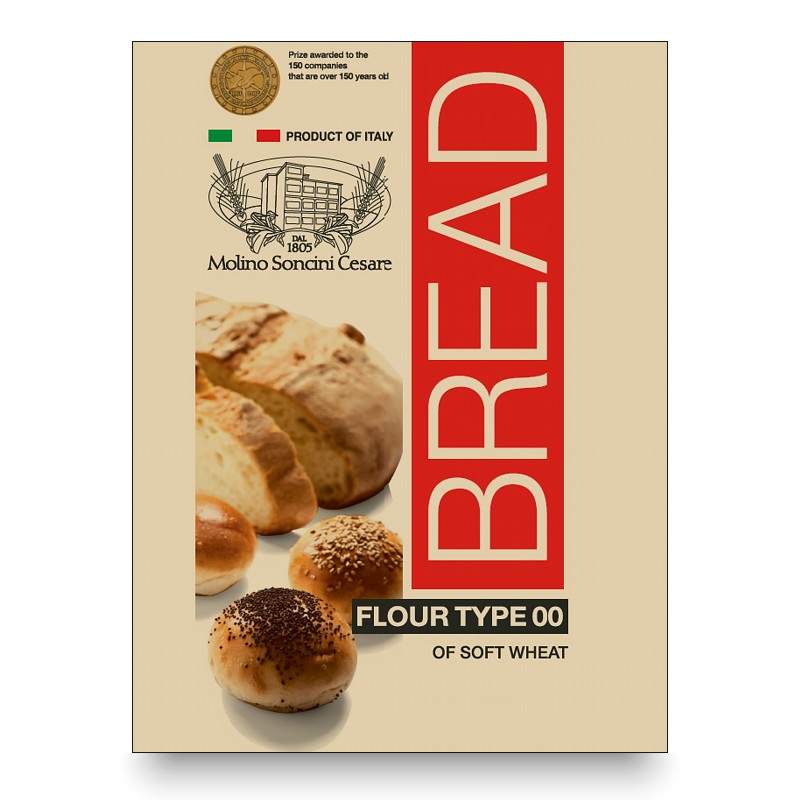

type-00RA for direct dough (4-6 hours)

Suitable for making Tuscan, Pugliese and Sicilian bread, and rolls.

I have been traveling now for 11 months, 21 days, 12 hours and 16 minutes. I have written thirteen letters and sent ten of them, and now I am working on the fourteenth letter. But it's not clear to me yet how it will turn out. My journey is nearly over, but I have the ever-stronger impression that a voyage that lasted a lifetime would still not be enough time to be able to say that I truly know Italy. Today, however, this thought is of little value, because you could say that – today – I have finally realised a dream of mine, and there is no-one else that I would like to tell it to. When I was young, and my teacher told us to write in our schoolbook the name of a city we wanted to visit, my classmates all chose New York, Paris and Toyko. Not me, I was the strange child who asked his father on the train to take him to Italy, to take him to Turin. While teaching me how to roll and roll out dough, my father would tell me about Napoleon, who decided to organise a withdrawal and allocate vehicles just so as to be able to transport grissini. I listened raptly, imagining a city in which the columns and pillars were made of bread and where, in winter, it would snow breadcrumbs. Turin is impressive, and walking with your head in the clouds, dazzled by the thousand things there are to see around every corner at any time of day, the city has so much to offer you: the exhibitions, the concerts, the libraries, the theatres, and the literary salons that seem to have their doors permanently half-open, so that you can have a peek inside. But in fact, the houses are not made of grissini, and you can say that I was slightly disappointed with this, just like my hope of bumping into you here by chance in one of these streets, between the used book-stalls under the porticos of one of the squares. But I could swear that I did see you, in front of a monument from 1800 that houses the Museum of Cinema, you were queuing up to go in; you were wearing a blue suit and knee-length boots. I would also swear that it was you again, later on, in piazza Castello, studying a map just like a tourist from the 1970s. I know, it's impossible that it was you. If you were here, you would never see this letter, and you would not know where to find me at Christmas, in just over a month from now. So instead, I hope to be able to meet you in Milan, so that I can end this journey not just with my words, but with our words together. A warm embrace L.

Grissini Rubatà Spread the flour out on a pastry board: melt the yeast and malt in a little tepid water, and add it to the flour, along with the rest of the water and the lard. Lastly, add the salt. Now begin to work the dough with your fingers until it becomes smooth, compact and shiny. Form it into a loaf, and leave it to rest in a deep pot, covered with a tea towel, for at least an hour. Next, with a knife, cut strips of the dough about 6cm long, and roll them with your fingers. Gently press down on the edges of each one, and make an incision down the middle. Place the “Rubatà” in a tray lined with baking paper, and cook for 20 minutes at 220°C. The result will be dry, crunchy and crisp grissini that stay good for days.

Rubatà is a prestigious type of grissini, eaten across Piedmont, but typical of Langhe and the province of Turin. History tells us that they are the oldest form of grissini, made for the first time in 1679 at the court of the House of Savoy by the court baker, Antonio Brunero. He was told by the royal doctor Teobaldo Pecchio to create this “very-cooked bread” for the future king Victor Amadeus II, a man of poor health who could not digest breadcrumbs. They were extremely successful, and even Napoleon Bonapart wanted the "petits bâtons de Turin" (“little Torinese sticks”) brought to Paris. Their name comes from "robat", an agricultural tool used to level off the land, and they are made by rolling the risen dough over on itself, in order to obtain the compact form full of knots that we are familiar with. This type of grissini is excellent with cold cuts and cheese, and are perfect alongside the world-renowned wines of Piedmont.